Excerpt from smithsonianmag.com

In the hunt for alien life, our first glimpse of extraterrestrials may be in the rainbow of colors seen coming from the surface of an exoplanet.

That’s the deceptively simple idea behind a study led by

Siddharth Hegde at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany.

Seen from light-years away, plants on Earth give our planet a

distinctive hue in the near-infrared, a phenomenon called red edge.

That’s because the chlorophyll in plants absorbs most visible light

waves but starts to become transparent to wavelengths on the redder end

of the spectrum. An extraterrestrial looking at Earth through a

telescope could match this reflected color with the presence of oxygen

in our atmosphere and conclude there is life here.

|

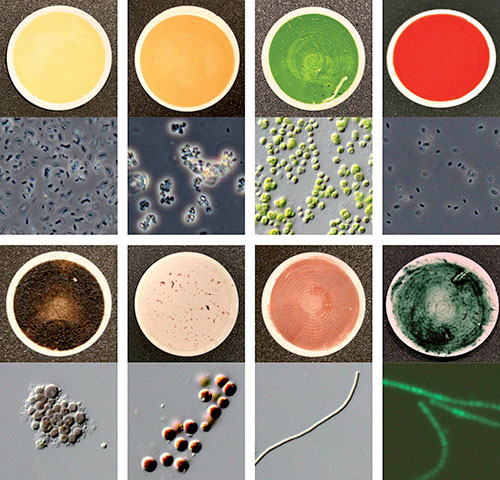

| Eight of the 137 microorganism samples used to measure biosignatures for the catalog of reflection signatures of Earth life forms. In each panel, the top is a regular photograph of the sample and the bottom is a micrograph, a version of the top image zoomed-in 400 times. |

Plants, though, have only been around for 500 million years—a

relative blip in our planet’s 4.6-billion-year history. Microbes

dominated the scene for some 2.5 billion years in the past, and some

studies suggest they will rule the Earth again

for much of its future. So Hegde and his team gathered 137 species of

microorganisms that all have different pigments and that reflect light

in specific ways. By building up a library of the microbes’ reflectance

spectra—the types of colors those microscopic critters reflect from a

distance—scientists examining the light from habitable exoplanets can have a plethora of possible signals to search for, the team argues this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“No one had looked at the wide range of diverse life on Earth and

asked how we could potentially spot such life on other planets, and

include life from extreme environments on Earth that could be the ‘norm’

on other planets,” Lisa Kaltenegger,

a co-author on the study, says via email. “You can use it to model an

Earth that is different and has different widespread biota and look how

it would appear to our telescopes.”

To make sure they got enough diversity, the researchers looked at temperate-dwelling microbes as well as creatures that live in extreme environments like deserts, mineral springs, hydrothermal vents or volcanically active areas.

While it might seem that alien life could take a huge variety of forms—for instance, something like the silicon-based Horta from Star Trek—it’s

possible to narrow things down if we restrict the search to life as we

know it. First, any life-form that is carbon-based and uses water as a

solvent isn’t going to like the short wavelengths of light far in the

ultraviolet, because this high-energy UV can damage organic molecules.

At the other end of the spectrum, any molecule that alien plants (or

their analogues) use to photosynthesize won’t be picking up light that’s

too far into the infrared, because there’s not enough energy at those

longer wavelengths.

In addition, far-infrared light is hard to see through an

Earth-like atmosphere because the gases block a lot of these waves, and

whatever heat the planet emits will drown out any signal from surface

life. That means the researchers restricted their library to the

reflected colors we can see when looking at wavelengths in the visible

part of the spectrum, the longest wavelength UV and short-wave infrared.

The library won’t be much use if we can’t see the planets’

surfaces in the first place, and that’s where the next generation of

telescopes comes in, Kaltenegger says. The James Webb Space Telescope,

scheduled for launch in 2018, should be able to see the spectra of

relatively small exoplanet atmospheres and help scientists work out

their chemical compositions, but it won’t be able to see any reflected

spectra from material at the surface. Luckily, there are other planned

telescopes that should be able to do the job. The European Extremely

Large Telescope, a 40-meter instrument in Chile, will be complete by

2022. And NASA’s Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope, which is funded

and in its design stages, should be up and running by the mid-2020s.

Another issue is whether natural geologic or chemical processes

could look like life and create a false signal. So far the pigments from

life-forms look a lot different from those reflected by minerals, but

the team hasn’t examined all the possibilities either, says Kaltenegger.

They hope to do more testing in the future as they build up the digital

library, which is now online and free for anyone to explore at biosignatures.astro.cornell.edu.

Source Article from http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/AscensionEarth2012/~3/tEbfaOuQMUs/this-alien-color-catalog-may-help-us.html

This Alien Color Catalog May Help Us Spot Life on Other Planets

No comments:

Post a Comment